Camille Flammarion

Camille Flammarion | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Nicolas Camille Flammarion 26 February 1842 Montigny-le-Roi, France |

| Died | 3 June 1925 (aged 83) Juvisy-sur-Orge, France |

| Spouses | |

| Relatives | Ernest Flammarion (brother) |

Nicolas Camille Flammarion FRAS[1] (French: [nikɔla kamij flamaʁjɔ̃]; 26 February 1842 – 3 June 1925) was a French astronomer and author. He was a prolific author of more than fifty titles, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science fiction novels, and works on psychical research and related topics. He also published the magazine L'Astronomie, starting in 1882. He maintained a private observatory at Juvisy-sur-Orge, France.

Biography

[edit]

Camille Flammarion was born in Montigny-le-Roi, Haute-Marne, France. He was the brother of Ernest Flammarion (1846–1936), the founder of the Groupe Flammarion publishing house. In 1858 he became a professional at computery at the Paris Observatory. He was a founder and the first president of the Société astronomique de France, which originally had its own independent journal, BSAF (Bulletin de la Société astronomique de France), which was first published in 1887. In January 1895, after 13 volumes of L'Astronomie and 8 of BSAF, the two merged, making L’Astronomie its bulletin. The 1895 volume of the combined journal was numbered 9, to preserve the BSAF volume numbering, but this had the consequence that volumes 9 to 13 of L'Astronomie can each refer to two different publications five years apart.[2]

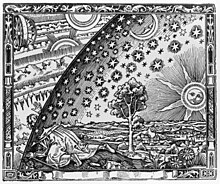

The "Flammarion engraving" first appeared in Flammarion's 1888 edition of L’Atmosphère. In 1907, he wrote that he believed that dwellers on Mars had tried to communicate with Earth in the past.[3] He also believed in 1907 that a seven-tailed comet was heading toward Earth.[4] In 1910, for the appearance of Halley's Comet, he was widely but falsely reported as believing the gas from the comet's tail "would impregnate [the Earth’s] atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet".[5]

As a young man, Flammarion was exposed to two significant social movements in the western world: the thoughts and ideas of Darwin and Lamarck and the rising popularity of spiritism with spiritualist churches and organizations appearing all over Europe. He has been described as an "astronomer, mystic and storyteller" who was "obsessed by life after death, and on other worlds, and [who] seemed to see no distinction between the two".[6]

He was influenced by Jean Reynaud (1806–1863) and his Terre et ciel (1854), which described a religious system based on the transmigration of souls believed to be reconcilable with both Christianity and pluralism. He was convinced that souls after the physical death pass from planet to planet and progressively improve at each new incarnation.[7] In 1862 he published his first book, The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds, and was dismissed from his position at the Paris Observatory later the same year. It is not quite clear if these two incidents are related to each other.[8]

In Real and Imaginary Worlds (1864) and Lumen (1887), he "describes a range of exotic species, including sentient plants which combine the processes of digestion and respiration. This belief in extraterrestrial life, Flammarion combined with a religious conviction derived, not from the Catholic faith upon which he had been raised, but from the writings of Jean Reynaud and their emphasis upon the transmigration of souls. Man he considered to be a “citizen of the sky,” other worlds “studios of human work, schools where the expanding soul progressively learns and develops, assimilating gradually the knowledge to which its aspirations tend, approaching thus evermore the end of its destiny.”[9]

His psychical studies also influenced some of his science fiction, where he would write about his beliefs in a cosmic version of metempsychosis. In Lumen, a human character meets the soul of an alien, able to cross the universe faster than light, that has been reincarnated on many different worlds, each with its own gallery of organisms and their evolutionary history. Other than that, his writing about other worlds adhered fairly closely to then current ideas in evolutionary theory and astronomy. Among other things, he believed that all planets went through more or less the same stages of development, but at different rates depending on their sizes.

The fusion of science, science fiction and the spiritual influenced other readers as well; "With great commercial success he blended scientific speculation with science fiction to propagate modern myths such as the notion that “superior” extraterrestrial species reside on numerous planets, and that the human soul evolves through cosmic reincarnation. Flammarion's influence was great, not just on the popular thought of his day, but also on later writers with similar interests and convictions."[10] In the English translation of Lumen, Brian Stableford argues that both Olaf Stapledon and William Hope Hodgson have likely been influenced by Flammarion. Arthur Conan Doyle's The Poison Belt, published 1913, also has a lot in common with Flammarion's supposed worries that the tail of Halley's Comet would be poisonous for earth life.

Family

[edit]Camille was a brother of Ernest Flammarion and Berthe Martin-Flammarion, and uncle of a woman named Zelinda. His first wife was Sylvie Petiaux-Hugo Flammarion,[11] and his second wife was Gabrielle Renaudot Flammarion, also a noted astronomer.

Mars

[edit]Beginning with Giovanni Schiaparelli's 1877 observations, 19th-century astronomers observing Mars believed they saw a network of lines on its surface, which were named "canals" by Schiaparelli. These turned out to be an optical illusion due to the limited observing instruments of the time, as revealed by better telescopes in the 1920s. Camille, a contemporary of Schiaparelli, extensively researched the so-called "canals" during the 1880s and 1890s.[12] As American astronomer Percival Lowell, he thought the "canals" were artificial in nature and most likely the "rectification of old rivers aimed at the general distribution of water to the surface of the continents."[13] He assumed the planet was in an advanced stage of its habitability, and the canals were the product of an intelligent species attempting to survive on a dying world.[14]

Halley's Comet

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (December 2024) |

When astronomers announced that the Earth would pass through the tail of Halley's Comet in May 1910, Flammarion was widely reported, in numerous American newspapers, as believing that toxic gases in the tail might "possibly snuff out all life on the planet".[15]

In an article in the New York Herald in November 1909, responding to such claims by others, he stated that "The poisoning of humanity by deleterious gases is improbable", and correctly stated that the matter in the comet's tail is so tenuous that it would have no noticeable effect.[16] However, he also indulged in a "thought experiment" about what might happen if it did inject various gases into the atmosphere. Sensation-seeking papers chose to quote only the latter part, leading to the widespread misconception that Flammarion actually believed it.

On 1 February 1910, Flammarion published an update in the Herald, saying he wished to warn journalists against "accusing me of announcing the end of the world for May 19 next. The end of the world will not occur on May 19 next."[17]

He could not have made his position any clearer, yet many papers ignored this rebuttal, and continued a campaign of misquoting and fabrication for the sake of sensational headlines. Flammarion was, in fact, the victim of a deliberate character assassination, in order to sell papers.[citation needed]

Psychical research

[edit]

Flammarion approached spiritism, psychical research and reincarnation from the viewpoint of the scientific method, writing, "It is by the scientific method alone that we may make progress in the search for truth. Religious belief must not take the place of impartial analysis. We must be constantly on our guard against illusions." He was very close to the French author Allan Kardec, who founded Spiritism.[18]

Flammarion had studied mediumship and wrote, "It is infinitely to be regretted that we cannot trust the loyalty of mediums. They almost always cheat".[19] However, Flammarion, a believer in psychic phenomena, attended séances with Eusapia Palladino and claimed that some of her phenomena were genuine. He produced in his book alleged levitation photographs of a table and an impression of a face in putty.[20] Joseph McCabe did not find the evidence convincing. He noted that the impressions of faces in putty were always of Palladino's face and could have easily been made, and she was not entirely clear from the table in the levitation photographs.[21]

His book The Unknown (1900) received a negative review from the psychologist Joseph Jastrow who wrote "the work's fundamental faults are a lack of critical judgment in the estimation of evidence, and of an appreciation of the nature of the logical conditions which the study of these problems presents."[22]

After two years investigation into automatic writing he wrote that the subconscious mind is the explanation and there is no evidence for the spirit hypothesis. Flammarion believed in the survival of the soul after death but wrote that mediumship had not been scientifically proven.[23] Even though Flammarion believed in the survival of the soul after death he did not believe in the spirit hypothesis of Spiritism, instead he believed that Spiritist activities such as ectoplasm and levitations of objects could be explained by an unknown "psychic force" from the medium.[24] He also believed that telepathy could explain some paranormal phenomena.[25]

In his book Mysterious Psychic Forces (1909) he wrote:

This is very far from being demonstrated. The innumerable observations which I have collected during more than forty years all prove to me the contrary. No satisfactory identification has been made. The communications obtained have always seemed to proceed from the mentality of the group, or when they are heterogeneous, from spirits of an incomprehensible nature. The being evoked soon vanishes when one insists on pushing him to the wall and having the heart out of his mystery. That souls survive the destruction of the body I have not the shadow of a doubt. But that they manifest themselves by the processes employed in séances the experimental method has not yet given us absolute proof. I add that this hypothesis is not at all likely. If the souls of the dead are about us, upon our planet, the invisible population would increase at the rate of 100,000 a day, about 36 millions a year, 3 billions 620 millions in a century, 36 billions in ten centuries, etc.—unless we admit re-incarnations upon the earth itself. How many times do apparitions or manifestations occur? When illusions, auto-suggestions, hallucinations are eliminated what remains? Scarcely anything. Such an exceptional rarity as this pleads against the reality of apparitions.[26]

In the 1920s Flammarion changed some of his beliefs on apparitions and hauntings but still claimed there was no evidence for the spirit hypothesis of mediumship in Spiritism. In his 1924 book Les maisons hantées (Haunted Houses) he came to the conclusion that in some rare cases hauntings are caused by departed souls whilst others are caused by the "remote action of the psychic force of a living person".[27] The book was reviewed by the magician Harry Houdini who wrote it "fails to supply adequate proof of the veracity of the conglomeration of hearsay it contains; it must, therefore, be a collection of myths."[28]

In a presidential address to the Society for Psychical Research in October 1923 Flammarion summarized his views after 60 years of investigating paranormal phenomena. He wrote that he believed in telepathy, etheric doubles, the stone tape theory and "exceptionally and rarely the dead do manifest" in hauntings.[29] He was also a member of the Theosophical Society.[30]

Legacy

[edit]He was the first to suggest the names Triton and Amalthea for moons of Neptune and Jupiter, respectively, although these names were not officially adopted until many decades later.[31] George Gamow cited Flammarion as having had a significant influence on his childhood interest in science.[32]

Honors

[edit]Named after him

- Flammarion (lunar crater)[33]

- Flammarion (Martian crater)[34]

- Asteroids: 1021 Flammario is named in his honour.[35]: 88 In addition, 154 Bertha commemorates his sister;[35]: 27 169 Zelia commemorates his niece;[35]: 28 141 Lumen is named after Flammarion's book Lumen: Récits de l'infini;[35]: 26 286 Iclea for the heroine of his novel Uranie;[35]: 38 and 605 Juvisia after Juvisy-sur-Orge, France, where his observatory is located.[35]: 60

- In 1897, he received the Prix Jules Janssen, the highest award of the Société astronomique de France, the French astronomical society.[36]

- He was made a Commandeur de la Legion d'honneur.[37]

Works

[edit]- La pluralité des mondes habités (The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds), 1862.[38]

- Real and Imaginary Worlds, 1865.

- God in nature, 1866. Flammarion argues that the mind is independent of the brain.

- L'atmosphère: Des Grands Phenomenes, 1872. (Appears to be an earlier edition of L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire 1888 which does not have the Flammarion engraving).

- Récits de l'infini, 1872 (translated into English as Stories of Infinity in 1873).[39]

- Lumen,[40] a series of dialogues between a man and a disembodied spirit which is free to roam the Universe at will. The novel includes observations about the implications of the finite velocity of light, and many images of otherworldly life adapted to alien circumstances.

- History of a Comet

- In Infinity

- Distances of the Stars, 1874. Popular Science Monthly V.5, Aug 1874. Translated in English from La Nature. (available online)

- Astronomie populaire, 1880. His best-selling work, it was translated into English as Popular Astronomy in 1894.

- Les Étoiles et les Curiosités du Ciel, 1882. A supplement of the L'Astronomie Populaire works. An observer's handbook of its day.

- De Wereld vóór de Schepping van den Mensch, 1886. A paleontological work.

- L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire, 1888.

- Uranie,[41] 1889 (translated into English as Urania in 1890).[42]

- La planète Mars et ses conditions d'habitabilité, 1892.

- La Fin du Monde (The End of the World), 1893 (translated into English as Omega: The Last Days of the World in 1894), is a science fiction novel about a comet colliding with the Earth, followed by several million years leading up to the gradual death of the planet, and has recently been brought back into print. It was adapted into a film in 1931 by Abel Gance.

- Stella (1897)

- L’inconnu et les problèmes psychiques (published in English as: L’inconnu: The Unknown), 1900, a collection of psychic experiences.

- Mysterious psychic forces: an account of the author's investigations in psychical research, together with those of other European savants, 1907[43]

- Astronomy for Amateurs, 1904

- Thunder and Lightning, 1905

- Death and its mystery—proofs of the existence of the soul; Volume 1—Before death, 1921

- Death and its mystery—proofs of the existence of the soul; Volume 2—At the moment of death, 1922

- Death and its mystery—proofs of the existence of the soul; Volume 3—After death, 1923

- Dreams of an Astronomer, 1923

- Haunted houses, 1924

Source: "Gallica search results". Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Obituary Notices: Fellows:- Flammarion, Camille". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 86: 178. 1926. Bibcode:1926MNRAS..86R.178.. doi:10.1093/mnras/86.4.178a.

- ^ "Which l'Astronomie?". Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- ^ "Martians Probably Superior to Us; Camille Flammarion Thinks Dwellers on Mars Tried to Communicate with the Earth Ages Ago". The New York Times. 10 November 1907. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

Prof. Lowell's theory that intelligent beings with constructive talents of a high order exist on the planet Mars has a warm supporter in M. Camille Flammarion, the well-known French astronomer, who was seen in his observatory at Juvisy, near Paris, by a New York Times correspondent. M. Flammarion had just returned from abroad, and was in the act of reading a letter from Prof. Lowell.

- ^ "Flammarion's Seven Tailed Comet". Nelson Evening Mail. 30 July 1907. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ "Ten Notable Apocalypses That (Obviously) Didn't Happen". Smithsonian magazine. 12 November 2009. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

The New York Times reported that the noted French astronomer, Camille Flammarion believed the gas "would impregnate that atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet".

- ^ James A. Herrick (2008). Scientific Mythologies: How Science and Science Fiction Forge New Religious Beliefs. InterVarsity Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8308-2588-2.

- ^ Reynaud, Jean (1806–1863) - The Worlds of David Darling

- ^ Andre Heck (2012). Organizations and Strategies in Astronomy. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 193. ISBN 978-94-010-0049-9.

- ^ Camille Flammarion's Collection Archived 9 January 2013 at archive.today

- ^ James A. Herrick (2008). Scientific Mythologies: How Science and Science Fiction Forge New Religious Beliefs. InterVarsity Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8308-2588-2.

- ^ M. Dinorben Griffith and Madame Camille Flammarion, "A Wedding Tour in a Balloon" Strand Magazine (January 1899): 62–68.

- ^ Flammarion, Camille (1892). La Planète Mars et Ses Conditions d'Habitabilité (in French). Paris: Gauthier-Villars et Fils.

- ^ Flammarion 1892, p. 589

- ^ Flammarion 1892, p. 586

- ^ "Comet's Poisonous Tail" (PDF). New York Times. 8 February 1910.

- ^ Goodrich, Richard J. (2023). Comet Madness: How the 1910 Return of Halley's Comet (Almost) Destroyed Civilisation. Prometheus Books. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-63388-856-2.

- ^ Goodrich, Richard J. (2023). Comet Madness: How the 1910 Return of Halley's Comet (Almost) Destroyed Civilisation. Prometheus Books. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-63388-856-2.

- ^ in "Death and Its Mystery", 1921, 3 volumes. Translated by Latrobe Carroll (1923, T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd. London: Adelphi Terrace.). Partial online version at Manifestations of the Dead in Spiritistic Experiments Archived 6 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pearson's Magazine. Volume 20. Issue 4. Pearson Publishing Company. 1908. p. 383

- ^ Camille Flammarion. (1909). Mysterious Psychic Forces. Small, Maynard and Company. pp. 63–135

- ^ Joseph McCabe. (1920). Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud?: The Evidence Given By Sir A. C. Doyle and Others Drastically Examined. London, Watts & Co. p. 57. "The impressions of faces which she got in wax or putty were always her face. I have seen many of them. The strong bones of her face impress deep. Her nose is relatively flattened by the pressure. The hair on the temples is plain. It is outrageous for scientific men to think that either "John King" or an abnormal power of the medium made a human face (in a few minutes) with bones and muscles and hair, and precisely the same bones and muscles and hair as those of Eusapia. I have seen dozens of photographs of her levitating a table. On not a single one are her person and dress entirely clear of the table."

- ^ Joseph Jastrow. (1900). The Unknown by Camille Flammarion. Science. New Series, Vol. 11, No. 285. pp. 945–947.

- ^ Alfred Schofield. (1920). Modern Spiritism: Its Science and Religion. P. Blakiston's Son & Co. pp. 32–101

- ^ Camille Flammarion. (1909). Mysterious Psychic Forces. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 406–454. ISBN 978-0766141254

- ^ Sofie Lachapelle. Investigating the Supernatural: From Spiritism and Occultism to Psychical Research and Metapsychics in France, 1853–1931. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1421400136

- ^ Lewis Spence. (2003). Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. Kessinger Publishing. p. 337. ISBN 978-1161361827

- ^ James Houran. (2004). From Shaman to Scientist: Essays on Humanity's Search for Spirits. Scarecrow Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0810850545

- ^ Harry Houdini. (1926). Haunted Houses by Camille Flammarion. Social Forces. Vol. 4, No. 4. pp. 850–853.

- ^ Raymond Buckland. (2005). The Spirit Book: The Encyclopedia of Clairvoyance, Channeling, and Spirit Communication. Visible Ink Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-1578592135

- ^ A. Merritt (2004). The Moon Pool. Wesleyan University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8195-6706-2.

- ^ "Camille Flammarion". Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ "George Gamow on Flammarion". Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Camille Flammarion". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- ^ Rabkin, Eric S. (2005). Mars: A Tour of the Human Imagination. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 91. ISBN 978-0275987190.

- ^ a b c d e f Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). "(1021) Flammario". Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 88. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_1022. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- ^ "Prix Janssen". Société astronomique de France. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Touchet, E. (1925). "Les Obseques de Camille Flammarion". L'Astronomie (in French). 39: 309–314. Bibcode:1925LAstr..39Q.309T.

- ^ "Pluralite des mondes habites: Etude ou l'on expose les conditions d'habitabilite des terres". Didier. 1872.

- ^ French Tales of Infinity - Astrobiology Magazine

- ^ ""LUMEN" BY CAMILLE FLAMMARION - AUTHORISED TRANSLATION FROM THE FRENCH". Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 19 November 2006.

- ^ Urania.

- ^ The Net Advance of Physics: History and Philosophy: Camille Flammarion

- ^ "Mysterious psychic forces: An account of the author's investigations in psychical research". 17 December 1907.

External links

[edit]- Works by Camille Flammarion in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Camille Flammarion at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Camille Flammarion at the Internet Archive

- Works by Camille Flammarion at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Atlas cèleste, Paris 1877 at AtlasCoelestis.com]

- Camille Flammarion at Library of Congress, with 102 library catalogue records

- Camille Flammarion at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Camille Flammarion at IMDb

- Newspaper clippings about Camille Flammarion in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1842 births

- 1925 deaths

- 19th-century apocalypticists

- 19th-century French novelists

- 19th-century French male writers

- 20th-century apocalypticists

- 20th-century French astronomers

- 20th-century French male writers

- 19th-century French astronomers

- French balloonists

- French male novelists

- French science fiction writers

- French parapsychologists

- People from Haute-Marne

- Writers from Grand Est

- Reincarnation researchers