Irori

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (August 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

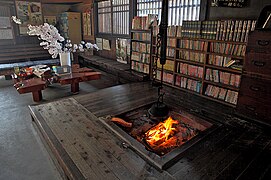

An irori (囲炉裏, 居炉裏) is a traditional Japanese sunken hearth fired with charcoal. Used for heating the home and for cooking food, it is essentially a square, stone-lined pit in the floor, equipped with an adjustable pothook – called a jizaikagi (自在鉤) and generally consisting of an iron rod within a bamboo tube – used for raising or lowering a suspended pot or kettle by means of an attached lever which is often decoratively designed in the shape of a fish.[1] Historically irori served as the main source of residential heating and lighting, providing a place to cook, dry clothing, and serve as a communal gathering location.

Function

[edit]The irori (囲炉裏) has the following functions.

- Residential heating

- The irori was generally located in the center of the room and used for heating the whole room.[2]

- Cooking

- The irori was used for cooking[2]. A jizaikagi (自在鉤) was used for hanging a pot over the fire. Fish and other food items were often skewered and stuck into ashes around the fire. They could also be buried in the ashes to be grilled. Sometimes a sake-filled tokkuri was heated by burying it in the ashes. In the Hokuriku region, cooking was done with irori until the kamado (cooking stoves) became widespread in the 1950s. In warm western Japan, people have disliked using irori during the summer and have used kamado and irori separately depending on the seasons from a long time ago.

- Lighting

- The irori was used for lighting at night.[2] In the pre-modern period, when fire was the primary illumination source, irori could safely light up rooms. In ancient times, only oil and candles were used for lighting.

- Drying

- The irori was used for drying clothes, food, raw wood, etc. by using hidana (wood lattice) hung from the ceiling over the irori or clothing racks placed by the irori.

- Source for making fire

- The fire in the irori was kept burning, and used for the source for making a fire of kamado or lighting equipments especially during the time without matches.

- A place for family communication

- The irori functioned as a place where a family gathers.[2] During meals and the night, people naturally gathered around irori and had conversations. Generally, each members of the family had a fixed place to sit, and irori functioned as a place to reaffirm the hierarchical order within the family. The names of each seats around the irori vary, but some examples include yokoza, kakaza, kyakaza, kijiri, or geza.[3] The seat farthest from the doma (the entryway) named yokoza was the seat of family head, the children sat in the seat closest to the doma named kajiri. The guests and the head's wife sat on both sides of these seats.[3]

- Improvement of the durability of the house

- The irori fills the room with warm air, which lowers the moisture content in the wood and makes it less susceptible to decay. In addition, the tar (wood tar) contained in the smoke from burning wood permeates the beams and thatched roof making them insect resistant and waterproof. However, the smoke in the house can also cause eye disease and other health problems.

Hazards

[edit]Similar to kerosene heaters common in rural Japan, burning charcoal produces fine particulates and carbon monoxide, the latter which can pose immediate health hazards in a poorly ventilated space. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter has been implicated in elevated rates of glaucoma and cataracts.[4] High rates have been observed among smokers and rural Indian farmers who practice stubble burning.[5]

Gallery

[edit]-

Irori

-

An actively used irori

-

Small irori

-

A jizaikagi hearth hook with fish-shaped counterbalance

-

An irori in use

-

An irori in a train station waiting room, 2010

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Fahr-Becker (2001), p. 196

- ^ a b c d 野本, 寛一 (2011). 食の民俗辞典 [Folk custom dictionary of food]. 柊風舎. p. 537.

- ^ a b 鎌田和宏 監修 (2013-02-05). 絵でわかる社会科事典3 昔のくらし・道具 [Picture dictionary of social study 3, Lifestyles and tools in the past]. 株式会社学研教育出版. p. 16.

- ^ "Fine Particulate Matter and Age-Related Eye Disease: The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science: 6. 2021-08-09. doi:10.1167/iovs.62.10.7. PMC 8354031.

- ^ ESMAP.2020. "The State of Access to Modern Energy Cooking Services (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group". World Bank. Retrieved 2022-10-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

References

[edit]- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele (2001) [2000]. Ryokan - A Japanese Tradition. Cologne: Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. ISBN 3-8290-4829-7.